Science and Application of Ferromagnetism, Paramagnetism, and Diamagnetism

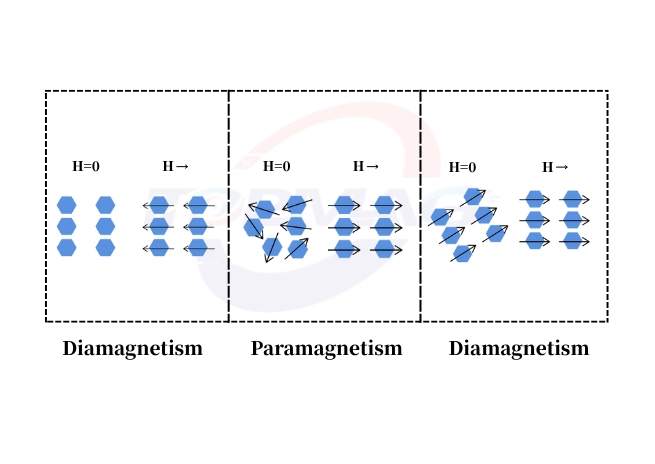

Magnetism is a unique physical phenomenon that takes place when a substance is influenced by an external magnetic field. It comes from the structure and motion of electrons in atoms or molecules. Materials may be characterized on the basis of their behavior in a magnetic field into the following three groups: ferromagnetic, paramagnetic, and diamagnetic. The nature of a material from each category is mainly determined by the electronic configuration and the physical properties.

Ferromagnetism

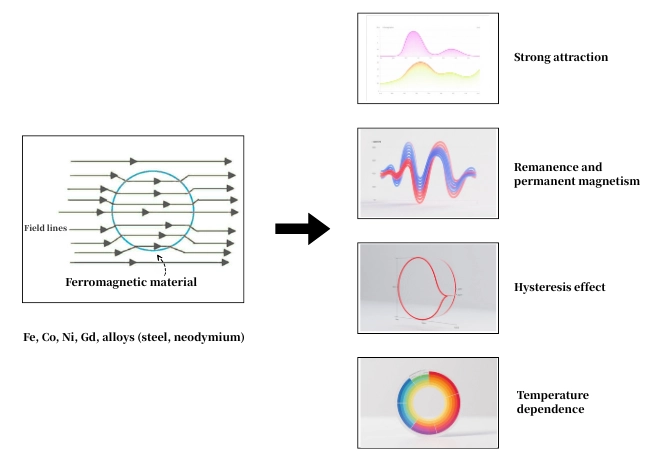

Ferromagnetic materials are known for their strong attraction to magnetic fields and persistent magnetism. This property is due to the net magnetic moment of unpaired electrons in the material and the tiny regions formed by the parallel arrangement of a large number of atomic magnetic moments – magnetic domains. When there is no external magnetic field applied, the magnetic domains are oriented randomly, and hence the net magnetic field is zero. However, if an external magnetic field is introduced, then the magnetic domains get instantly aligned, and the material shows a big magnetic response; thus, it becomes magnetically strong.

1.Typical Materials

Iron (Fe), cobalt (Co), nickel (Ni), gadolinium (Gd), and alloys such as steel and neodymium (NdFeB, commonly used as a strong magnet).

Iron: Iron is one of nature’s most abundant metals, and its name comes from the Latin word “ferrium” and the English word “ferromagnetism.” Its magnetism owes its origin to the unpaired electron spins in its atomic structure, thus giving rise to a microscopically natural property of permanent magnetism. Its most significant contribution is during steel making, in which alloying with elements such as carbon further develops its strength and hardness.

Cobalt: Cobalt was even named “cobalt blue” due to its enchanting deep blue pigment. However, only the surface can be peeled by the knowledge of the real magic of cobalt. Being a ferromagnetic metal, the strength and stability of cobalt magnetism have a range of applications in high-tech fields. Most of the time, it is mined together with nickel and copper. In other words, it is a grayish lustrous metal, but under today’s popular technologies, it holds a position of great importance. One application contains cobalt in lithium-ion batteries, where lithium cobalt oxide is used as the active material for several rechargeable batteries for mobile phones, laptops, and electric vehicles, ensuring efficient operation and safety due to its stability.

Nickel: Nickel is one of the “big three” ferromagnetic elements and belongs to the same transition metal family as iron and cobalt. Due to its appealing silver-white luster and excellent ductility, it has extensive applications. One of the most famous uses of nickel is in stainless steel, which contributes to a kind of steel that is resistant to corrosion and high temperatures.

Gadolinium: Neodymium is another rare earth element whose ferromagnetism exhibits remarkable strength when alloyed. Pure neodymium is only paramagnetic on its own. Still, when combined with iron and boron, it forms neodymium magnets, among the most powerful permanent magnets currently available. These magnets possess extremely high magnetic fields, capable of lifting objects nearly a thousand times their own weight.

Neodymium: Neodymium in alloy form exhibits strong ferromagnetism. Pure neodymium is paramagnetic; in combination with iron and boron, it forms neodymium magnets. These magnets have extremely high magnetic field strengths, allowing them to lift loads nearly a thousand times their actual weight. They are widely used in many applications, from small devices such as headphones to large ones, including wind turbines. Because of their small size and high efficiency, they have become widely used in modern electronics.

2.Characteristics

Strong attraction: Ferromagnetic materials exhibit strong attraction to both the north and south poles of a magnet, enough to attract heavy objects or drive mechanical motion.

Remanence and permanent magnetism: After the external magnetic field is removed, some magnetic domains remain aligned, the material retains magnetism (remanence), and some materials can even become permanent magnets.

Hysteresis effect: The magnetization process of ferromagnetic materials has a “memory” characteristic, and the magnetization strength is related to the magnetic field history, which is crucial in electromagnetic devices.

Temperature dependence: Above a certain temperature (Curie temperature), thermal motion destroys the alignment of magnetic domains, and ferromagnetism turns into paramagnetism.

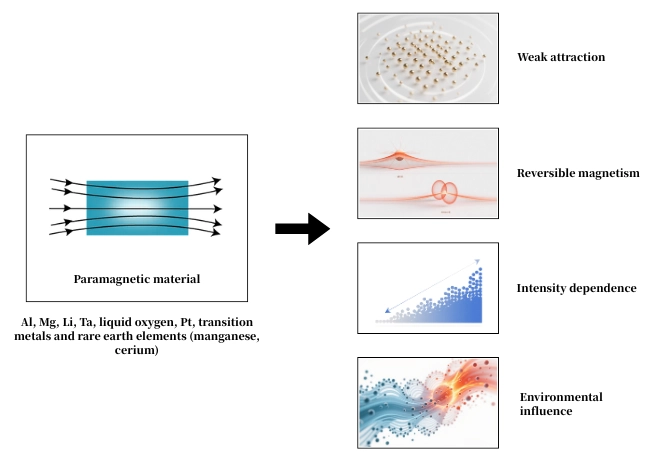

Paramagnetism

1.Typical materials

Weak attraction: Paramagnetic materials have a very weak attraction, and usually require precision instruments (such as magnetic balances) to detect.

Reversible magnetism: After the magnetic field is removed, thermal motion quickly restores the dipoles to a disordered state, and the magnetism disappears completely.

Intensity dependence: The magnetization intensity is proportional to the strength of the external magnetic field. The more unpaired electrons there are, the more significant the paramagnetism.

Environmental influence: Thermal motion weakens at low temperatures and paramagnetism increases; at high temperatures weaken magnetism weakens.

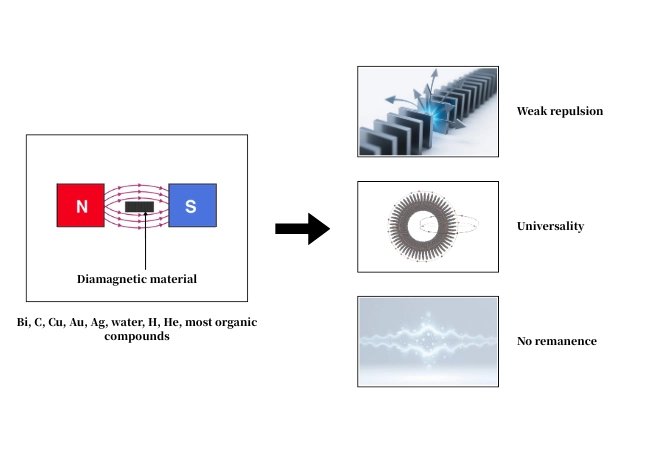

Diamagnetism

1.Typical materials

Bismuth (Bi, strong diamagnetic), carbon (C), copper (Cu), gold (Au), silver (Ag), water, hydrogen (H), helium (He), and most organic compounds.

2.Characteristics

Weak repulsion: diamagnetic materials are pushed to areas with weaker magnetic fields. The repulsion effect is more obvious under strong magnetic fields, and some materials can even achieve magnetic levitation.

Universality: All substances are diamagnetic, but they are often masked in ferromagnetic or paramagnetic materials.

No remanence: After the magnetic field is removed, the diamagnetic effect disappears immediately, and no magnetism remains.

Conclusion: Infinite possibilities in the magnetic world

Ferromagnetism, paramagnetism, and diamagnetism show the diverse behaviors of materials in magnetic fields, which are derived from subtle differences in electronic structure. From the strong magnetic force of ferromagnetic materials driving the industrial revolution, to the sensitive response of paramagnetic materials assisting scientific research, to the subtle repulsion of diamagnetic materials opening up levitation technology, the unique properties of magnetic materials have not only deepened our understanding of the nature of matter, but also provided infinite possibilities for the future development of science and technology and society. Whether in precision instruments in laboratories or in high-tech devices in our daily lives, magnetic materials are quietly shaping our world.

I'm dedicated to popular science writing about magnets. My articles mainly focus on their principles, applications, and industry anecdotes. Our goal is to provide readers with valuable information, helping everyone better understand the charm and significance of magnets. At the same time, we're eager to hear your opinions on magnet-related needs. Feel free to follow and engage with us as we explore the endless possibilities of magnets together!